The debut issue of The Bournemouth Journal is available in print-on-demand at Amazon.

Poetry Example:

Caitlin Kendall

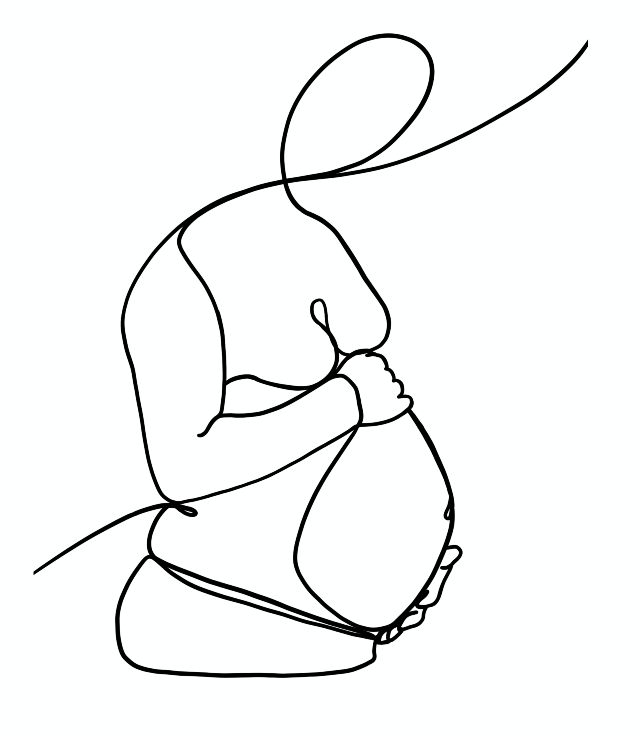

For Nora

We do not yet know her newly formed head

with eyes like stars only just arrived. And

yet her body is imbued with motion in the womb

like a butterfly, upon which all our attention is now drawn,

fluttering in this most beautiful dance.

In time her mother’s breast will begin to ache

flower blooming in her pelvis from

that portal between worlds.

In time her heart will be known to us

within the loving comfort of our arms

glowing like the amber embers of home fires.

We will be remade in the light of her gaze

like the dawn: for there is no history

after birth and everything is changed.

Short Story Example:

Before I Go

By Anthony O’Donovan

The long beige corridors reminded Mairéad of school as she hurried to follow Paula’s brisk step and rapid chat.

“He’s recently had a hip operation. And he’s with us until he’s back on his feet,” said the nurse as they stopped outside a door. “Ha. Literally,” she added with a smile before knocking and walking straight in.

“Well, Joe. How are we today?”

Mairéad felt like an intruder stepping into the room which was large enough to accommodate a bed and a sofa where a man, dressed in a dark blue suit, sat reading a day-old newspaper with deep interest.

“Joe?” said Paula raising her voice and waving until he peered at them with a start, his eyes magnified by his glasses.

“Oh,” said the man, carefully putting the paper down and working at something in his ears.

“He turns off his hearing aid when he doesn’t want to be disturbed, but then forgets,” said the woman in an unnecessarily quiet voice flaring her eyes conspiratorially.

“Well,” said the man, glaring at them. “It’s about time.”

“How are we today, Joe?”

“I don’t know how you are,” he said. “But I’ve been waiting. I’m looking forward to my smoke.”

“This is Mairéad, she’ll go with you on your walk.”

Joe gave the girl a long appraising look taking in the cherry red Dr Martens, the black leggings under a dark satin and lace dress, the smoky eyeliner, and lastly the top knot and her red-dyed undercut.

“What happened to Louise?”

“Louise is on leave today and we’ve Mairéad here on work experience this week.”

“Did you have a death?” he asked, pointing vaguely with a crooked finger at the girl’s dress.

“A death?” said Mairéad, startled. “Eh, no.”

“Black is the in colour, Joe,” said the nurse.

The man shook his head and looked at Paula and then back to the girl.

“Work experience? You want to be a care worker or a… a nurse?”

“Oh no, eh. I’ve to do this for school.”

Joe nodded thoughtfully. “Just a secondment then,” he said, using the metal walker positioned nearby to lever himself upright with a groan. When he was steady on his feet, framed by the walker, he was surprisingly tall and thin and his suit hung loosely on him, giving the impression that he’d borrowed it. He jerked himself along towards the door.

“Right. Forward march. But I warn you, I could do the mile in four and a half minutes. I’ll leave you behind if you can’t keep up.”

With his eyes on his feet, as he moved, Joe pushed the walker forward and then shuffled along behind. Mairéad had to back out of the doorway as Joe approached and kept going. Paula indicated with her head for the girl to follow him and she had to slow her natural cadence to match the pace of his two-step rhythm along the corridor.

“Do you have a nickname?” he asked.

“Nickname?”

“Yes. What your company calls you?”

“My company?”

“You know, your mates. You do have friends, don’t you?”

“Eh, yeah. They just call me Mairéad.”

“How disappointing. Everyone should have a nickname.”

At the end of the corridor, double doors opened out onto a large rectangular garden where manicured low shrubs and plants featured in the centre surrounded by a wide concrete path. A ramp ushered them from the building, and they ambled their way along the grounds.

“My auntie Trish calls me marmalade.”

“Not the same. Your family name you for themselves. Your pals name you for who you are. Like me, I’m Brolly.”

Noticing his breath had become ragged with the effort, she wondered what she should do if he collapsed, and a cold shiver of fear jangled her spine.

“Maybe you should take it easy, eh, Brolly. No need to show off.”

Joe looked sideways at her as he took his next steps. “Nearly there,” he said, breathing heavily. “Final push.”

At the end of the garden was a bench in a sunny patch sheltered by shrubbery and partially hidden from the care home by a pink hydrangea. Joe pulled up the walker onto the grass and eased himself onto the seat. With a sense of relief, Mairéad sat down beside him. Sitting in the peaceful space, Joe’s breathing became less raspy.

“Not quite a mile,” he said after a few moments. “But not bad.”

“Not bad at all, Brolly.” She smiled at him and sat back on the bench. “So, why are you called Brolly then?”

“Oh,” he said, looking pleased. “From when I was in the RAF. You see, it’s what we’d call a parachute. I was a test pilot, so I’d fly the new planes. Often, there’d be something wrong with them and I’d have to ditch them. Then I’d need my brolly. That and being from Ireland. When I’d go home, they’d tell me not to forget my brolly, as a sort of joke.”

“You were a pilot? Did you fight in the Battle of Britain?”

Joe snorted. “I was only five during the war.”

“Oh, right. Sorry.”

“No, I was there long after. I grew up here, but there was nothing for me in Ireland then and I wanted to be a pilot. So, I took the boat over and joined up.”

He pulled out a leather pouch where he kept his tobacco and pipe which took a minute or two to fill with swollen knuckles and unsteady hands. Several layers of the loose leaves needed to be laid and tamped with a finger in the pot. Once he was happy with the consistency in the chamber, Joe got the dark mass glowing using the flame of a thin silver lighter and several large puffs.

“I love the smell of pipe smoke,” said Mairéad.

“They don’t like it here. I’ve to do it outside and even with that they tell me it’s bad for me.”

“Well, they’re not wrong, are they?” She looked back along the empty path towards the main building. “Think I’ll have a smoke with you,” she said, taking out a packet of tobacco with papers and rolled herself a cigarette.

Joe watched fascinated. “That isn’t that wacky-backy is it?”

Mairéad scoffed. “No, just a rollie. Can I borrow a light?”

She awkwardly lit her cigarette with the side-ways flame of his pipe lighter. The time passed gently as they sat and smoked in their own ways. Joe with a sequence of three puffs of the pipe, while Mairéad took occasional pulls of the rollie and then retrieved any loose tobacco left on her lips.

“If you don’t want to be a nurse, what do you want to be?”

“I haven’t thought about it really.”

“I couldn’t wait to be a pilot. Of course, it wasn’t what I imagined it would be.”

“I’ve never had that feeling, of wanting to be something.”

“It’ll probably happen at some stage. One day you’ll see someone at their work and think: I want to do that.”

“Maybe,” she said, squinting her eyes against the smoke that erupted from her mouth as she spoke.

“It was going to the cinema that did it for me. If we’d three clean jam jars, we’d get in for free. Cowboy pictures were everyone else’s favourite. But I just loved anything with aeroplanes.”

Joe’s expert hands worked the pipe like a musical instrument. He’d put his fingers over the pot to stoke it. There was a small tool he used to rake the dottle and regulate the tobacco burn. And the blue-white plumes issued from the side of his mouth. Mairéad was surprised at how long a fill of the pipe lasted as she was making another rollie.

“Pity it’s not wacky-baccy. I’d have liked to try some,” said Joe. “I knew some fellows did it in the sixties and what have you. They said they enjoyed it. But I was always too afraid. Now, I think I’d like to have seen what all the fuss was about. You know, before I go.”

Mairéad scrutinised Joe’s profile and he could feel her stare, so he turned to her. She checked that they couldn’t be seen and pulled out a neatly folded clear plastic bag which unfurled in her hand revealing, what looked like, small florets of dried broccoli inside.

“Well, as it happens,” she said. “I do have some herb with me, only a little. My just-in-case stash.”

“Herb?”

Mairéad raised her eyebrows to indicate the significance.

“Oh,” he said, thinking for a moment. “It isn’t illegal anymore?”

The girl made a face. “Some things are still the same, but this is nothing like anything your buddies would’ve had back in the day.”

He had a strange silent open-mouthed laugh throwing his head back and closing his eyes. Mairéad could see that most of his teeth were lost or rotten. Then he tapped the pipe against the edge of the seat to knock the smouldering tobacco from the bowl and handed it over.

“Well, let’s be having some,” he said.

Using a pipe was new to Mairéad, but she filled the chamber with the brown-green clusters and, using Joe’s lighter, demonstrated taking in the puffs of smoke and letting them sit for a moment before breathing out.

“I mix some Rosemary from Mum’s kitchen into it. It adds a nice taste,” she said, refilling the pipe and handing it to Joe.

He tentatively raised it to his lips with the lighter at the ready. “Here goes,” he said before igniting the leaves and taking short pulls of smoke.

“Now, hold it in,” urged Mairéad. “Hold it in.”

He pursed his lips and kept his breath still while Mairéad supervised until, with a slight cough, he breathed out expelling white wisps from his mouth.

“You, OK?” she asked searching his face.

He looked puzzled as if trying to work out some difficult problem. Then as if the answer came to him, his eyes widened. “Rosemary,” he said. And a smile appeared on his face which looked so odd to Mairéad that she burst into laughter.

They were so engrossed in chatter that Paula surprised them when she came to find them for lunch.

“Ah, good. I’m ravenous,” said Joe, easing himself up from the bench with the aid of the walker.

“Right, let’s get you back to the party,” said Mairéad.

Mairéad could hear the hoarse wheezing of Joe’s breath as they made their way back home. But this time it sounded natural; the way things were, and she didn’t worry.

“So, you’re here all week?” asked Joe.

“Yeah, supposed to be anyway.”

“Maybe we could…”

“Yeah, sure.”

“Why’s there no music?” demanded Mairéad, flicking through the radio channels. “Mum? Why’s it just boring people talking? Where’s the music?”

Her mother eased the car fractionally forward in the slow-moving line of traffic, sighed in answer, and then turned to watch a pedestrian march past.

“Right. I’m blue-toothing something,” said the girl, scrolling on her phone and pressing buttons on the stereo until loud bass-heavy hip hop blasted out.

“Mairéad!” her mother shouted.

A woman walking past turned to look. The girl lowered the sound with a wave to the passer-by, then threw her feet on the dashboard, the toe of her Dr Martens squeaking against the windscreen.

Her mother glared at her. “Do you think they’ll make you do bedpans today?” she asked and was rewarded with a murderous look from the girl. Smirking, she took in the jeans and light blue denim shirt her daughter was wearing. “And no black?”

“Oh, mum. They kept asking me all week who died so eventually I made up this story that my pet turtle was eaten by a dog. But oh, oh, then this one woman. Oh my god, she was so sweet. She gave me a big hug and I felt so bad for lying to her. And I decided not to go through all that today.”

Her mother surveyed her face as she sang along with the song on the stereo. “You’re enjoying work experience.”

Mairéad tutted. “Mum! Come on.”

Joe’s door was ajar and Mairéad knocked and walked in to find Paula and another nurse packing up his things.

“Oh, is he leaving then?” she asked.

She looked from the serious faces of the two women to the stripped bed with the small suitcase lying open on top and the dark blue suit folded neatly inside.

“Fuck,” she said as large gulpy sobs burst from her.

“I’m sorry, love,” said Paula, folding her into a hug. “He died last night.”

“I… I… I killed him,” she mumbled to Paula.

“Don’t be silly. He went peacefully in his sleep. He was elderly, it was his time that’s all.”

“You don’t understand…” said the girl, coming out of the hug with watery eyes and a red face.

Paula hushed Mairéad and, with an arm around her shoulder, started to bring her from the room telling her she’d make her a cup of tea. As they were leaving, Mairéad’s eyes landed on Joe’s pipe on the dresser.

“Could I have this?” she asked, picking it up.

Paula led the girl, with the pipe in hand, to the kitchen to have a milky tea with sugar and a chocolate biscuit.

“Find me, afterward, in the Day Room. There’s a resident I want you to meet.”

“No!” said Mairéad, her eyes becoming molten. “No, I don’t want to meet anyone else. I’ll do bedpans instead.”

Paula laughed. “We don’t get students to do bedpans,” she said. “Unless we don’t like them,” she added with a mischievous grin. “See you in the Day Room in fifteen minutes. OK?”

Mairéad sipped the tea and inspected Joe’s pipe, its peaty trace already on her fingers as she nibbled on a biscuit. A flash of movement caught her eye, and she looked up to see a woman with long grey hair tied up in a bun flapping her arms at her from the doorway.

“Come to the pantry,” she hissed to Mairéad, jerking her head to the left to indicate the direction.

Mairéad stared at her blankly.

“The pantry. See you in the pantry,” the woman said in a hoarse whisper, nodding to Mairéad to reinforce the words.

“Pantry?”

“Oh, for the love of…” said the woman, shaking her head. “The storage room at the end of the corridor. Meet us there in five minutes.”

“Wait, what?” said Mairéad, but the woman moved with a quick shuffle out of the kitchen.

The woman and her two companions were waiting for Mairéad in the pantry, their excited whispering faded on her arrival.

“We’re friends of Joe,” said Cathy, the woman with the grey bun.

“Oh,” said Mairéad. “So sorry for your loss.”

“Ah, he was a grouch,” said a white-haired woman who had a walking stick that she leaned on with both hands while standing.

“Brenda!” said Cathy, slapping her on the arm.

“Well, he was,” said Brenda, sniffing.

“Anyways, we hear you might be able to get us some Mary Jane,” said Cathy.

“Mary Jane?” asked Mairéad.

“Oh, for the love of… Like the nymph Echo. No voice of her own, just repeats the last of what I say,” said Cathy, rolling her eyes to her pals.

“Ah,” said Brenda. “You always complicate things, spouting two words when one would be fine. She means marijuana. My granddaughter used to supply me, but she went and got herself pregnant.” She closed her eyes and shook her head to emphasise the tragedy.

The air surrounding Mairéad seemed to curdle as she looked about the expectant faces and felt an unsettling in her stomach.

“So?” demanded Cathy. “Do you speak…” She turned to the others. “Does she speak English at all?”

“How would I know?” said Mick, the third of the trio looking accused.

Brenda turned to her two companions. “I think you broke her, Cathy. You and your Classics.”

“No, wait,” said Mairéad, shaking the anxiety from herself and putting the stem of Joe’s pipe into her mouth. “I don’t have much with me today,” she said taking out the neatly folded plastic bag. “But we should have a smoke in memory of Joe.”

“Who’s Joe?” asked Mick. Cathy slapped him on the arm.