aL Yhusuff

Disclaimer: The Bournemouth Journal has not read, reviewed, or been directly involved in the development of this work. This post is shared in recognition of the commitment of an independent author who has shown interest in the Journal’s community.

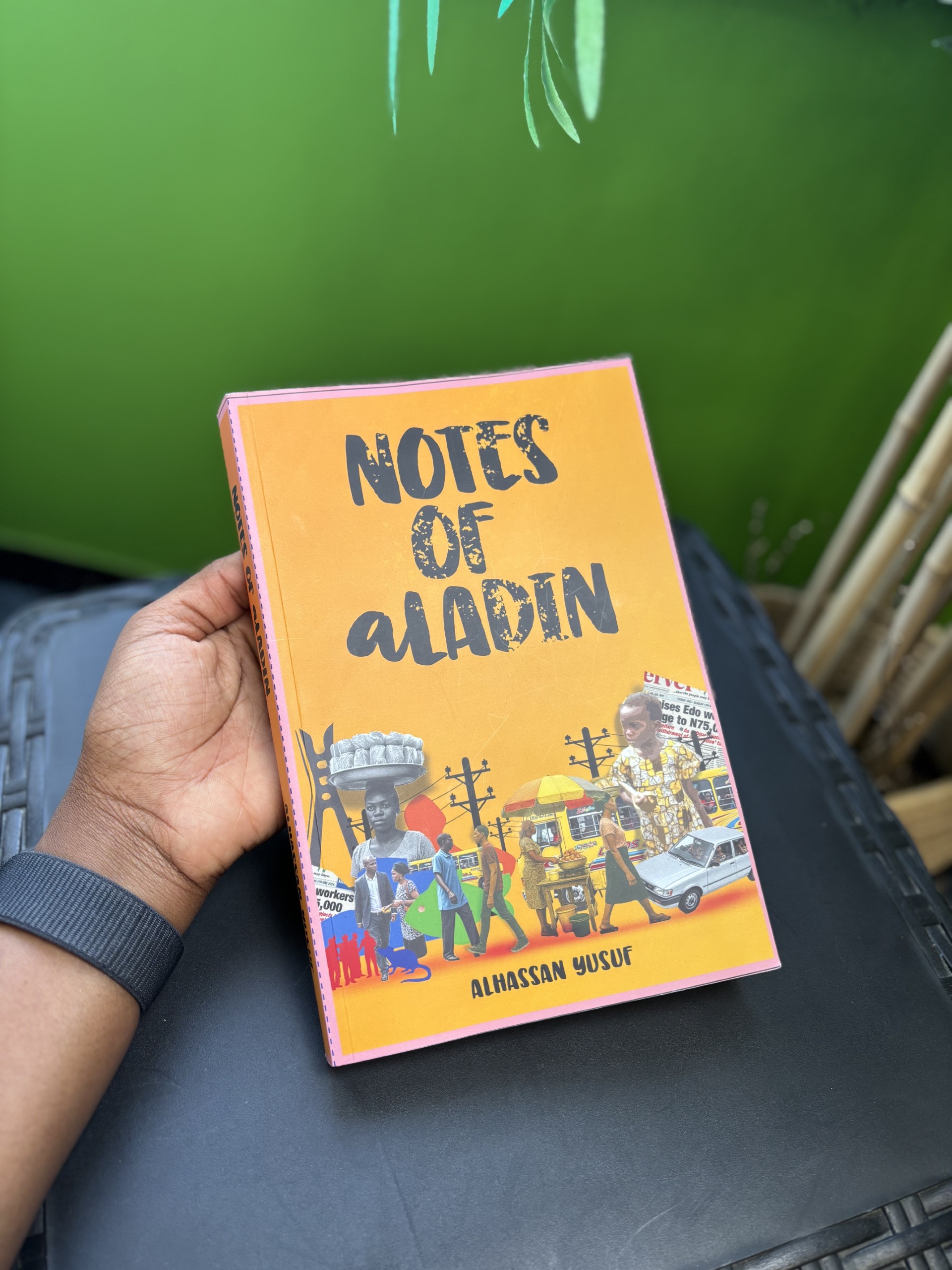

In an era defined by digital façades and curated perfection, my debut novel, Notes of aLadin, breaks through with gripping honesty and comedic grit. Written in journal-style entries that are both heartbreaking and hilarious, Notes of aLadin is a creative chronicle of a young Nigerian man’s survival in an economy that often seems rigged against the everyday dreamer.

Woven with cultural specificity, biting social commentary, and laugh-out-loud humour, Notes of aLadin traverses the highs and many lows of youth unemployment, failed dreams, fragile hope, and the resilience it takes to stay afloat in modern-day Nigeria.

From day one, we are introduced to aLadin, a jobless graduate with dreams bigger than his account balance, caught in the whirlwind of Nigeria’s unforgiving job market. Each diary-style entry takes the reader through moments that oscillate between despair and dark humour: the absurdity of job offers that require five years of experience for entry-level roles, the agony of borrowed data and unpaid electricity bills, the humiliation of roadside sales pitches, and the bittersweet highs of scoring freelance gigs that barely pay but feel like life rafts.

Notes of aLadin is captured with sharp wit and poetic self-awareness, offering a deeply human portrayal of what it means to “hope dangerously” in a society that rarely offers second chances.

At its core, Notes of aLadin is about the quiet dignity in everyday struggle. I used the character of aLadin to explore themes such as youth disenfranchisement, identity and self-worth in a capitalist world, mental health in harsh socioeconomic conditions, digital aspiration versus real-life despair, and the role of community and friendship in survival.

Though grounded in the Nigerian context, the themes are universal. Whether you are a graduate in Nairobi navigating the gig economy, a dreamer in Bournemouth juggling side hustles, or a middle-aged man in Mumbai looking for a second shot at life, Notes of aLadin will resonate. It is a multicultural bridge that connects readers across geographies through shared human experiences.

Notes of aLadin is embedded with the unapologetic use of pidgin English, local slang, and culturally rich metaphors that make the text authentic yet accessible. It speaks directly to the unemployed graduate, the burnt-out worker, the struggling entrepreneur, and the hopeful writer with a cracked phone and cracked dreams, but also to the executive who remembers starting from nothing.

It is not just a story; it is a movement, a literary voice for a generation that often goes unheard.

While Notes of aLadin lays bare the frustrations of everyday Nigerian life, it also shows the triumphs of small wins. The reader witnesses aLadin evolve from rejection letters and N75.19 bank balances to earning his first $30 from a foreign client, and later juggling freelance gigs and food delivery operations.

After writing this book, I had to dedicate it to the nine-year-old who still believes he can be anything, and the thirty-two-year-old just trying to stay afloat.

Excerpt

Day 27 – I Got a Sales Job

I barely slept. Not because of excitement, but because mosquitoes turned my room into a blood donation camp. I had covered myself with my wrapper like I was in a do-or-die hide-and-seek game, yet those tiny demons still found a way to feast on me.

By 5 a.m., I gave up. Sat up, checked my phone. Nothing new.

The only thing in my bank account was hope, and last I checked, hope could not buy breakfast — not even Mama Ibeji’s akara, which I always got on credit.

But today was not just any day. Today, I was meeting Tomiwa’s uncle. My first real job lead in weeks.

I took my time freshening up. Used the last drops of my roll-on like it was some expensive cologne. Pulled out my best shirt — the one that still had a little dignity left. Iron? Who had light? I did the Nigerian special: smoothed it with my hands and hoped for the best.

At exactly 9 a.m., Tomiwa called.

“Guy, where you?”

“On my way.”

“Abeg, no fall my hand. This my uncle no get time.”

I hurried out, trekking because my transport budget was tears and vibes.

When I got to Tomiwa’s place, he gave me a once-over. “You sure say you wan impress my uncle with this your shirt?”

I looked down. “Wetin do am?”

Tomiwa sighed. “Nothing. Let’s go.”

The office was in a plaza at Allen. Small but decent. Tomiwa led me in, and we met his uncle, a serious-looking man in his forties, bald, with glasses perched on his nose.

“So, you’re the one looking for a job?” he asked, looking me up and down like I was an applicant on Who Wants to Be Employed?

“Yes, sir.”

Tomiwa jumped in. “Uncle, this guy sabi work. Any role, he go deliver.”

The man raised an eyebrow. “Any role?”

Tomiwa nodded confidently, as if he had just handed them Pep Guardiola in the form of a job seeker.

The uncle adjusted his glasses. “Have you worked in sales before?”

I swallowed. Sales? I was not expecting that. But a job is a job. “Well, I—”

“It’s commission-based,” he cut in. “No salary. You earn based on how much you sell.”

My heart sank. Again? Why was every job I found tied to commission-based suffering?

But Tomiwa was looking at me. Say yes, say yes! his eyes screamed.

I forced a smile. “Okay, sir.”

His uncle nodded. “You’ll be selling solar inverters. Can you convince people to buy?”

I had never even convinced myself to buy airtime when I was broke, but I nodded anyway. “Yes, sir.”

“Good. You’ll start tomorrow.”

That was it. No contract. No “We’ll get back to you.” Just “Start tomorrow.”

I left the office feeling confused.

Tomiwa grinned. “You see? I tell you I go run am for you.”

“Tomiwa,” I said slowly, “another commission-based job?”

He scratched his head. “Bro, no be say I no understand. But something is better than nothing.”

I knew he was right. I knew it. But I still felt like life was playing a wicked game with me.

I got home and lay on my bed, staring at the ceiling. Selling solar inverters.

How? Where? To whom?

Did I even have the mouth for this? The whole thing felt like a scam.

But then again, was not being broke the biggest scam of all?